We know what good depression treatment looks like. You probably won’t get it.

Approximately half of people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) also suffer from Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (Flory). That is my justification for treating depression in a blog primarily devoted to PTSD. Depression usually follows some of the earliest symptoms, such as anxiety and flashback but there are no fixed rules (https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/related/depression_trauma.asp).

As I’ve posted recently, it has become almost commonplace today, at least among those impressed by the latest results of neuroscience, to say that Descartes got it backward. Not “I think therefore I am,” but “I am therefore I think.” The mind is composed of body. Brain makes mind possible.

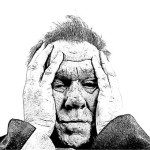

Yet, this is not how we experience ourselves. “I feel therefore I am” is probably the first and fundamental experience of self, or at least the experience that makes life worth living. It is the feeling of being alive. Depression is the opposite. It robs existence of vitality and pleasure. That’s the cardinal symptom of major depression; it can make life not worth living. Depressed people are about twenty times more likely to commit suicide (Gotlib and Hammen).

“Depression is the flaw in love”

A couple of recent books that take the neurological basis of depression seriously, also see love and its loss as central to the experience of depression. Because the mechanism of depression takes place in the brain, and because medication and other treatments that work on the brain help, doesn’t mean that our experience of the world is unimportant. Most important is loss, above all the loss of love: of being loved, of a loved one, as well as the loss of values crucial to one’s identity, such as the loss of religious belief.*

Depression is the flaw in love. To be creatures who love, we must be creatures who can despair at what we lose, and depression is the mechanism of that despair. When it comes, it degrades one’s self and ultimately eclipses the capacity to give or receive affection. It is the aloneness within us made manifest.

Love, though it is no prophylactic against depression, is what cushions the mind and protects it from itself. Medications and psychotherapy can renew that protection, making it easier to love and be loved, and that is why they work. (Solomon, p 15)

Medication and therapy make love possible. For what is the good of a more balanced mind if one has nothing of value to do with it? Generally, this love is of another person, but it can be love of one’s work, or faith.

Stress causes depression among the vulnerable. Surprisingly, humiliation is the greatest stressor, loss is the second. (Solomon, p 61). But perhaps they are not so different. Though we seldom think about it this way, loss is shaming. After loss we are exposed to the world, naked and alone. Once you experience a shaming loss, you will never be the same, for you will have learned something about your vulnerability that you may have sensed but never known.